By Hali Serrian

Sensei Ben Dawkins is one of Athens Yoshukai Karate’s most enthusiastic students. At Athens Yoshukai, he fulfilled a number of roles, including kickstarting the Tate classes, serving as Senior Instructor, and initiating the Instructor Apprentice discussions. Now he serves as Head Instructor for his own school, Upstate Yoshukai Karate. I thought there were some tidbits we could all learn from Sensei Dawkins, and so wanted to interview him about his martial arts experience. Here’s what I learned:

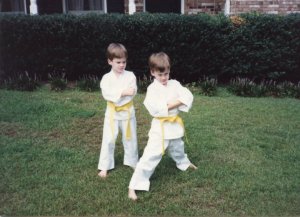

Sensei Dawkins is on the right

Hali Serrian: How long have you been studying martial arts?

Sensei Dawkins: I started martial arts at age 6, studying Tang Soo Do in the Atlanta area. I trained until I was 11 and about to take my first degree brown belt test (3rd keup). After we moved, I didn’t pick up the martial arts again for years.

HS: What first got you into Yoshukai karate?

SD: In 2010, I was talking with my friend Joel Dover, and the topic moved to martial arts. He told me a bit about Athens Yoshukai, and I mentioned that I would have gotten back into martial arts years ago if it wasn’t for the cost. He told me a bit more about the dojo’s not-for-profit philosophy, and I observed a class that night. I started the following fall, and I began training in Kyuki-do and Hapkido the following spring. A bit later, I also began studying Judo and IOKA kobudo.

HS: How have you participated in the WYKKO?

SD: Besides work in the Athens Yoshukai dojo, my participation in the WYKKO as a larger body has mainly been through the organization events and making friends with other WYKKO practitioners. Lately, teaching at Upstate Yoshukai, my dojo, has allowed me to become more directly involved in the WYKKO, and I look forward to being more involved as time goes by.

HS: What made you want to have your own dojo?

SD: I knew fairly early on that I would want to continue teaching martial arts. They’ve become so important to my everyday life that I can’t imagine not being involved. Teaching here in Spartanburg is a natural extension of that, and, for a pseudo-selfish reason, I wanted to continue actively training, so I found students I can train with!

HS: How did you decide what to charge for classes?

SD: First, I spoke with the director of the community center where I teach. I got a sense of the cost of the various activities at the center. I knew I couldn’t support free classes at this point in my professional/financial life, so I settled on $25, which seemed like a good figure–substantial enough to be serious, but inexpensive enough to incentivize starting right away.

HS: How would you like to see your dojo develop over time?

SD: Once finances allow, I would like to teach martial arts full time. As for my current program, I would like for it to continue to be an outreach for the martial arts in the area. I believe strongly in the martial arts as a way to build respectful, healthy, confident citizens, and I hope that Upstate Yoshukai will reach many, many students in the years to come.

HS: Do you have any advice for someone wanting to start their own dojo?

SD: The first important step for those who want to start their own dojo is to immediately partner with their instructors, who are a wealth of knowledge and can get the ball rolling much sooner than feeling blindly on your own. Ideally, you should have already been teaching and engaged actively with your home dojo. From there, pick a start date and get to teaching! There are so many aspects of being a head instructor that must be learned by direct experience. But, it is extremely difficult to get started without the help of an experienced instructor. There is no substitute for that kind of help.

HS: What are some of the differences in your teaching style when it comes to kids vs. adults?

SD: With adults/older youth, I am much more content/big picture oriented. Martial arts have such deep philosophical roots, and they are also engaged with anatomy, physiology, and kinesiology. I’ve found that many adults find this aspect fascinating, and when adults know why they’re doing the same kick hundreds of times, they’ll do it.

With kids, I couch a lot of training in games. They’ll be kicking, punching, blocking, and sweating, but as long as they’re smiling and happy, they’ll run until well after most adults are out of gas. I’ve found that content has to be introduced in a fun and engaging way–kids won’t do it if it’s not fun, even if they see the long-term benefit. I’ve found my enthusiasm is contagious with kids. Their parents really seem to enjoy how excited their kids get, as well.

HS: How has your teaching developed and changed over your years of instruction?

SD: It’s hard to describe how my teaching has changed because it’s a very fluid process. I’m an educator professionally as well, so I’m well in tune with pedagogical strategies and theory. In practice, I’m finding ways to engage each student at his/her personal wheelhouse. It’s hard to do, and it requires constant observation and empathy to really find what might excite one individual student vs. another. I strive always to be positive, but I want my students to know that I’m not going to accept mediocre effort. Not everyone is a natural athlete, but everyone can give his/her best effort.

HS: What are some of your best memories of martial arts?

SD: My best memories are of great classes, which inspire me greatly. There have been  days that I didn’t really feel like training, but 15 minutes into class, I’ve forgotten why I’m tired and I just get into the learning. I hope I always love class as much as I do. Big events and trips are fun, and I love being involved at that level, but amazing classes are really where it’s at for me.

days that I didn’t really feel like training, but 15 minutes into class, I’ve forgotten why I’m tired and I just get into the learning. I hope I always love class as much as I do. Big events and trips are fun, and I love being involved at that level, but amazing classes are really where it’s at for me.

HS: Can you tell us about some of the more difficult parts of your experience as a martial artist?

SD: My more difficult experiences with the martial arts have been at the hands of “bad tough guy” martial artists. I don’t mind intensity, and I don’t mind people who love fighting, practical training, and really painful techniques. I mind when a martial artist’s ego gets so wild that he/she has to tear down everyone else on the floor. Dealing with those experiences has always been hard, and whenever I feel myself getting a bit too “tough guy” in class, I remind myself how it feels to be treated like an inferior by someone who is supposed to be teaching.

Another big challenge was in the development of stamina and cardio. When I started martial arts, a tough class would really knock me on my behind. I’ve enjoyed working hard on my physical fitness, and I feel the benefits every day.

HS: What is your favorite weapon?

SD: My favorite weapon is the sai because it is also the weapon I have the most trouble with. I just want to make it awesome, so I work and work with the weapon. It feels so potentially effective, and they’re just fun to hold onto. Nunchaku is fun, and the bo is also beautiful in its line and requisite precision. But, to me, the sai is the weapon that requires the most skill to even start to use.

HS: What was your hardest test and why?

SD: My hardest test was my 3rd kyu green belt test. It wasn’t that the test was so much [more] difficult than others, but I was testing in a gymnasium at the East Athens Community Center, and it was so hot that for the most part, I had no idea where I was. It took everything I had to keep it together for that one!

HS: Your best test?

SD: My best test was my shodan test. It was the culmination of months of intense training, and I felt like I pushed myself to the edge to get my technique and conditioning ready. All of that work made the shodan testing experience so fantastic for me, and I’m really proud of how it turned out.

HS: When you don’t have time to train like you’d prefer, what do you do?

SD: If I only have time to run through a form or two, I’ll work through the rest in my head. It’s a process called eupraxia, and major psychological studies have shown that concentrated mental practice engages the same portions of the lateral cerebellum as the actual practice. Of course, it can’t all be mental practice, but until I can perform a technique, form, or combination in my head, I can’t be certain I really know it.

HS: Was there a moment when you knew you were going to stick with Yoshukai?

SD: I was a new blue belt at the first annual Athens/Clarke Yoshukai karate cabins. I was training hard in the grass by a lake, and I felt fantastic about the training and the people involved.

HS: Everyone knows you have an awesome knowledge of kiai. What’s one of the most common mistakes you see with kiai and what are the most important things to developing good kiai?

SD: I think most people think that kiai must first be loud. I disagree–loudness is a byproduct. Kiai has to originate from the core. Some will say “breathe from the diaphragm.” Again, I disagree. The diaphragm is an involuntary muscle, and an individual has very little control over that. Instead, I say focus on breathing as low as possible, from the abdominal muscles. That’s where efficient breath lives, and then from there, experiment with your most natural vocal range–like the pitch that comes out of you when you sigh. From there, set that sigh on fire and let it go. That’s a kiai, and if it’s born from that place, it will be loud, distinctive, and real.

HS: Is there some story that should go down as legendary from your martial arts experiences?

SD: There are a few that my training partners will tell–I don’t know if they’re legendary, but they’re definitely fun:

-I once ran a class where literally every student who walked in complained about how cold it was. I ran a warm-up until I saw condensation running down the mirrors, and then I asked if anyone felt cold. I still hear about that one.

-I remember a fight class where we all sweated so much that the floors were dangerously slick–that was a lot of fun, and I was extremely sore for the better part of a week.

-I remember watching a fellow student test for 1st kyu while running a pretty rough fever–he didn’t think I knew, but I was definitely impressed.

-I remember several instances of 1,000 jumping jack classes–the dread on newer students’ faces, and the pride of having done it, especially when we did more like 1500 jumping jacks.

-I remember the first time I saw Soke–the man looked like something out of a samurai movie.

HS: Anything else you think we should know?

SD: The WYKKO is a large enough organization to enjoy all of the benefits of camaraderie and excellent training. But, remember that it is also small enough that *you* can get involved in a substantive way. Think about how you want to get involved, and talk to you instructor about your options!

So there you have it! If you haven’t met Sensei Dawkins yet, be sure to next time he makes his way to Athens. He truly is a fountain of Yoshukai knowledge as well as a pretty cool guy in general.